What is Dada?

The bustling Dadaist Tristan Tzara declared Dada to be “not modern” but “anarchist” in its radical individualism and rejection of all dogmas. What did he mean by it? Clearly based on a belief in progress, modernism tried to work with the prevailing order to see its requests come true, whereas Dada worked against it. It is anything but easy to define Dada in a few words and in a simple way. This is mainly due to the fact that the Dadaist approach was inter- and transdisciplinary, collaborative, first European and later internationalist and aimed at a fundamental breach with traditions and conventions. This is why Dadaist art—at least at the time of its emergence—avoided established and affirmative channels of distribution and commercialization such as museums, the art market, and the publishing sector, taking care of its dissemination and visibility itself. Regardless of the movement’s heterogeneous character and the difficulty of categorizing it, we do know some things for certain such as Dada’s official place of foundation and a large number of involved artists and authors this website will shed light on by focusing on selected examples. In his manifest of 1918, Tzara expounded on the etymology of Dada as follows: “DADA—this is a word that throws up ideas so that they can be shot down; every bourgeois is a little playwright, who invents different subjects … DADA DOES NOT MEAN ANYTHING … We read in the papers that the negroes of the Kroo race call the tail of a sacred cow: DADA. A cube, and a mother, in a certain region of Italy, are called: DADA. The word for a hobby-horse, a children’s nurse, a double affirmative in Russian and Romanian, is also: DADA … Thus DADA was born, out of a need for independence, out of mistrust for the community. People who join us keep their freedom. We don’t accept any theories … Liberty: DADA DADA DADA;—the roar of contorted pains, the interweaving of contraries and all contradictions, freaks and irrelevancies: LIFE.” Another example of a radical attempt at definition from the echelons of the Dadaists is to be found in the magazine Der Dada (1919) published by Raoul Hausmann: answering the question “What is Dada?” with the questions “An art? A philosophy? a politics? Fire insurance? Or: State religion? Is dada actual energy? Or is it nothing, that means, everything?” suggested subversive answers critical of the zeitgeist. In 1923, Theo van Doesburg, accompanied by Kurt Schwitters, set out on a Dada campaign through Holland. A lengthy pamphlet offered for sale on this “propaganda” tour opened up leeway for interpretation by answering the question “Wat is Dada?” (What is Dada?) with such statements as “Dada is no art movement—Dada is a direct movement of life that turns against anything we regard as vital … do you now know what ‘Dada’ is?”

On 5 February 1916, a handful of artists, poets, and dancers who had immigrated into Switzerland from all four corners of the continent—Hans Arp, Hugo Ball, Emmy Hennings, Richard Huelsenbeck, Marcel Janco, Marcel Słodki, and Tristan Tzara—rang in Dadaism in the Cabaret Voltaire at no. 1 Spiegelgasse in Zurich. With the First World War raging in Switzerland’s European neighbouring countries, many people sought exile in neutral Switzerland for ideological, political, or—in the case of disabled veterans—health reasons. Dadaism’s “ism” was no negatively connoted label bestowed from outside like that of Impressionism, for instance, but was soon used by its protagonists who announced their Dada soirée on 14 July 1916 in the Züricher Post under the heading “Futurism, Dadaism, Cubism.” Today, historical Dadaism is rather strictly limited to the period from 1916 to 1925. Many of its followers turned to the Surrealist movement around André Breton from 1923/24 on. That Dadaism remained an underestimated art movement until the 1960s, i.e, its fiftieth anniversary, supposedly results from the ephemeral character of its works in the form of performances and works on paper, as well as from the quarrels within the group and its members’ selective denial of their artistic career for fear of being accused as Bolshevists—a rather popular reproach at the time. Observers on the outside were also embarrassed by the Dadaists’ sweeping assault on bourgeois and nationalist values as driving forces of the war through persiflage and the destruction of established linguistic and aesthetic norms. That Dadaism was frequently associated with Bolshevism and anarchism was anything but a suitable foundation for an acknowledgment of its achievements in the Cold War era. Nevertheless, people such as Felix Baumann and Hans Bolliger in Zurich, Georges Hugnet, Michel Sanouillet, and Robert Lebel in France, Arturo Schwarz in Milan, and Eberhard Roters and Hanne Bergius in Germany saw to it that the Dadaists’ heritage did not completely sink into oblivion in those years and drew increasing attention to it at universities, at museums, and in the art market from the 1960s. Since then, and particularly from the 1990s, major museums all over the world, like the Centre national d’art et de culture Georges-Pompidou in Paris, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, the Berlinische Galerie in Berlin, and not least the Kunsthaus Zürich have devoted important exhibitions to this crucial art movement. Dadaism can only be understood by contextualizing it in time. However, considering the far-reaching consequences of the First World War and its impact to date, an analysis of the Mouvement Dada is also more burning than ever today.

The Dada Collection at Kunsthaus Zürich

Dada and Zurich, Dada and the Kunsthaus Zürich—these were anything but spontaneous love affairs. The Dadaists were rather put up with in the city than welcomed with open arms, and it took several decades until “Dada products” found their way into the collection of the Kunsthaus. A first herald of today’s Dada collection at the Kunsthaus was the donation of three works by Sophie Taeuber from Hans Arp in 1958.

Exhibitions at the Kunsthaus, however, offered some sidelights and highlights on Dada and its immediate forerunners quite early on: Wilhelm Wartmann, the first director of the Kunsthaus, organized the exhibition Der Moderne Bund (The Modern Federation, 1912) two years after the institution’s opening, which, among others, included works by the later Dadaist Hans Arp. So Arp came to the Kunsthaus before Dada did. In 1919, the artists’ association “Das Neue Leben” (The New Life) presented not only “Gestaltungen” (designs) and “Stickereien” (embroideries) by Arp but also reliefs by Marcel Janco, “mechanomorphic” pictures by Francis Picabia, and Dada heads and puppets by Sophie Taeuber. The exhibition was accompanied by lectures on abstract art held by Tristan Tzara and Marcel Janco, for example. With the exhibitions Abstrakte und surrealistische Kunst (Abstract and Surrealist Art) of 1929, which featured a soirée with Arp and Schwitters in its accompanying program, and Abstrakte Malerei und Plastik (Abstract Painting and Sculpture) of 1934 Wartmann also focused on Dada.

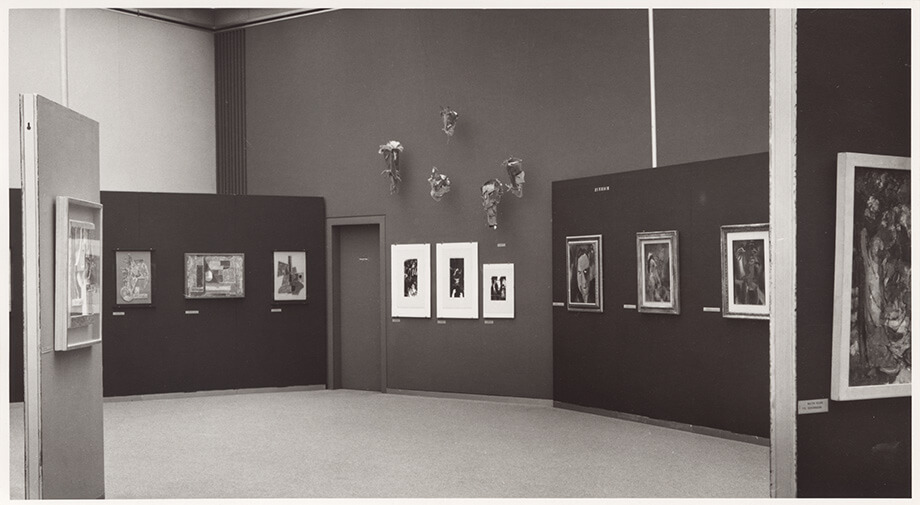

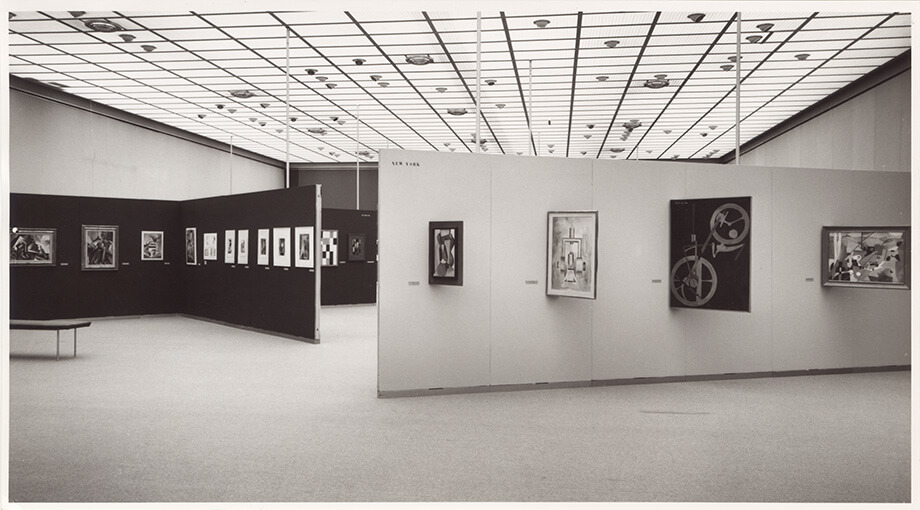

The Kunsthaus Zürich presented its first exhibition explicitly dedicated to Dada together with the Paris Musée national d’art moderne in the autumn of 1966 on the occasion of the fiftieth Dada anniversary. It was Felix Baumann who, as an assistant of René Wehrli, then director of the Kunsthaus, organized the show in Zurich, which then travelled to Paris. The two museums’ comprehensive Dada show was a response to initiatives by the Association Internationale pour l’Étude de Dada et du Surréalisme, which had been founded in 1964 by the Dada expert Michel Sanouillet (1924–2015) and Henri Béhar (b. 1940). The exhibition catalogue was issued as the second volume in this bustling Paris association’s publication series.

Exhibition 1966

Various individuals in Zurich were also committed to Dada: Carola Giedion-Welcker (1893 – 1979), Hans Bolliger (1915–2002), and Peter Schifferli (1921 – 1980). Their direct contacts and their friendship with Dadaists, their convincing collecting activities, and their engagement as regarded the media and the sphere of publishing made Dada become manifest. The inheritance the Kunsthaus Zürich had come into in 1966 was extended by further aficionados like Peter K. Wehrli and René Simmen in their special way.

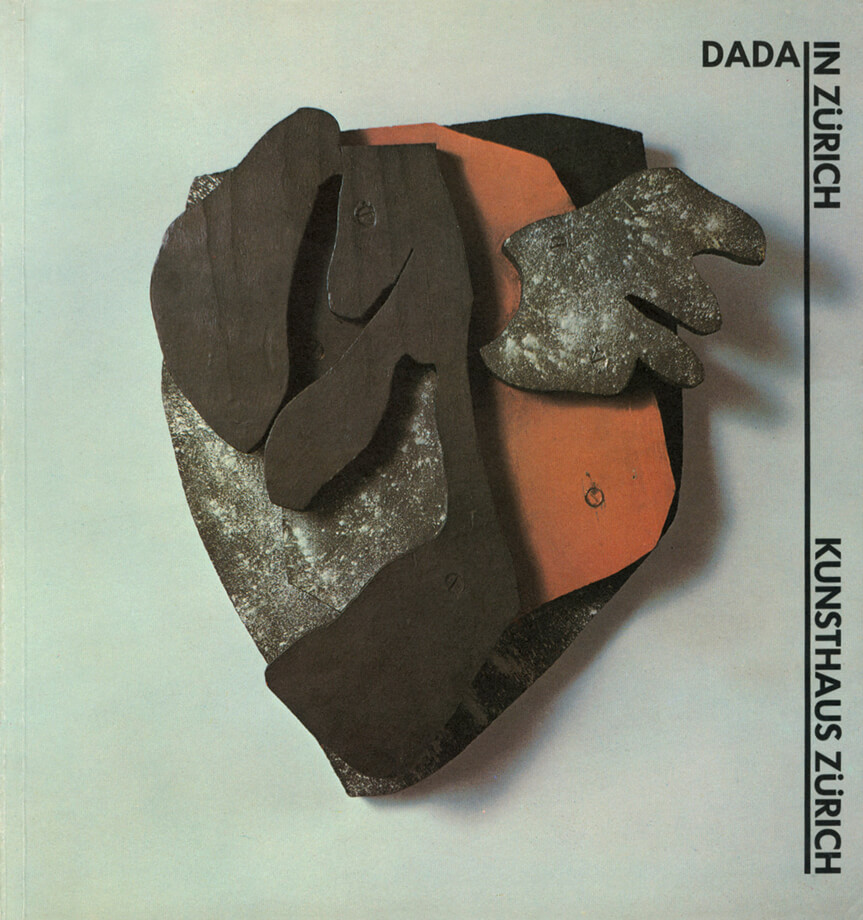

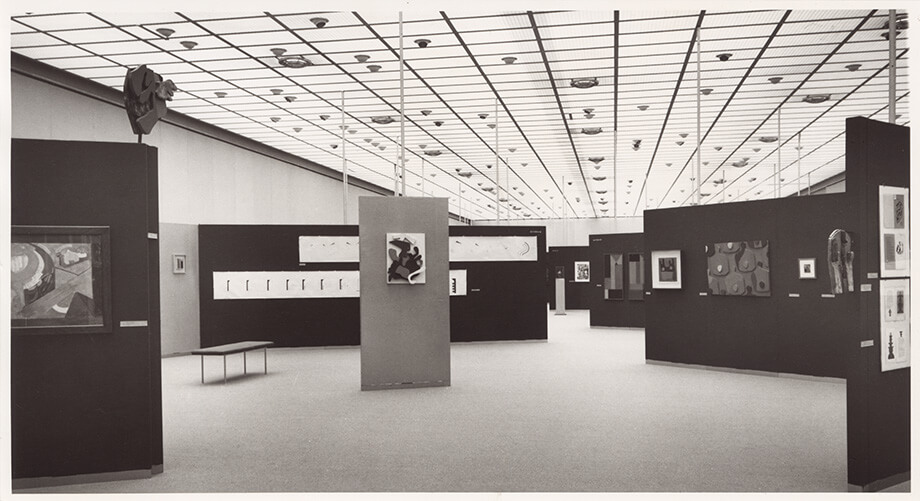

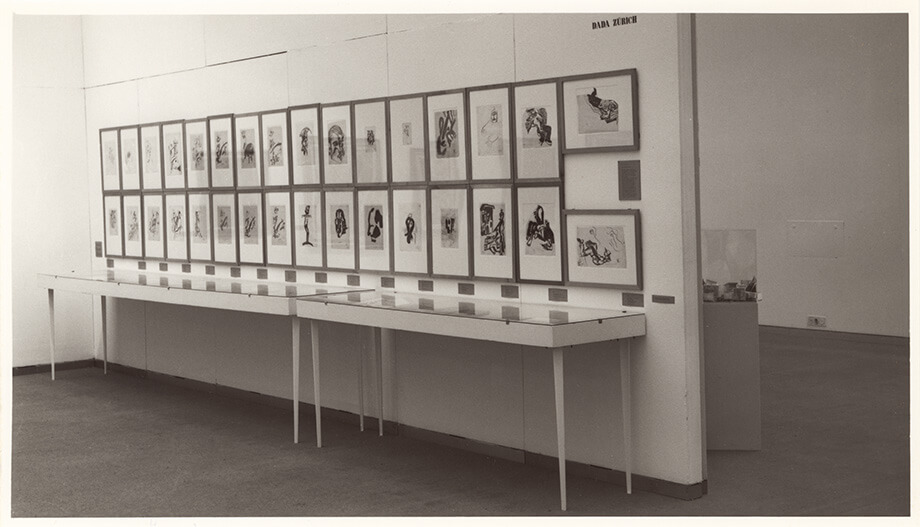

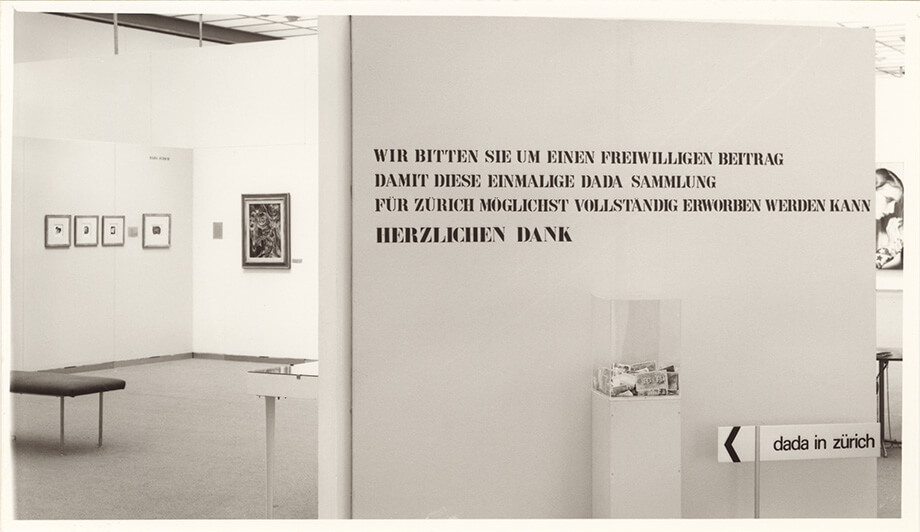

When parts of Tristan Tzara’s library and collection were sold at an auction of Kornfeld & Klipstein in Bern in 1968, the Kunsthaus Zürich still had to give the pas to the Milan collector and gallery owner Arturo Schwarz. Under the aegis of Felix Baumann, who was appointed director of the Kunsthaus in 1976, Dada became a true focus of the institution’s collecting activities, which reached their first peak in 1980: the exhibition Dada in Zürich presented itself as a Dadaist set of rules for interpretation and an acquisition operation all in one. Most of the more than one hundred and thirty works and nearly four hundred documents were put up for sale (the former mostly from the possession of Arturo Schwarz, the latter from Hans Bolliger’s collection). The event was aimed at permanently securing a share as large as possible for the collection of the Kunsthaus. Private donations amounting to a total of 1,183,000 Swiss francs, part of which were raised in a kettle campaign during the presentation, and public funds of 1,172,000 Swiss francs made it possible to acquire seventy large-format pictures, reliefs, collages, and drawings, as well as one hundred and thirty documents. These were rounded out by donations supplementing the former legacy of over thirty works from the estate of Hans Richter, which made the Kunsthaus Zürich a new center of collecting Dada art and of research in the field next to the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Centre Pompidou in Paris. Close contact with Hans Bolliger, who lent the Kunsthaus his support as a consultant, intermediary, and donator, played a decisive role in building up the collection.

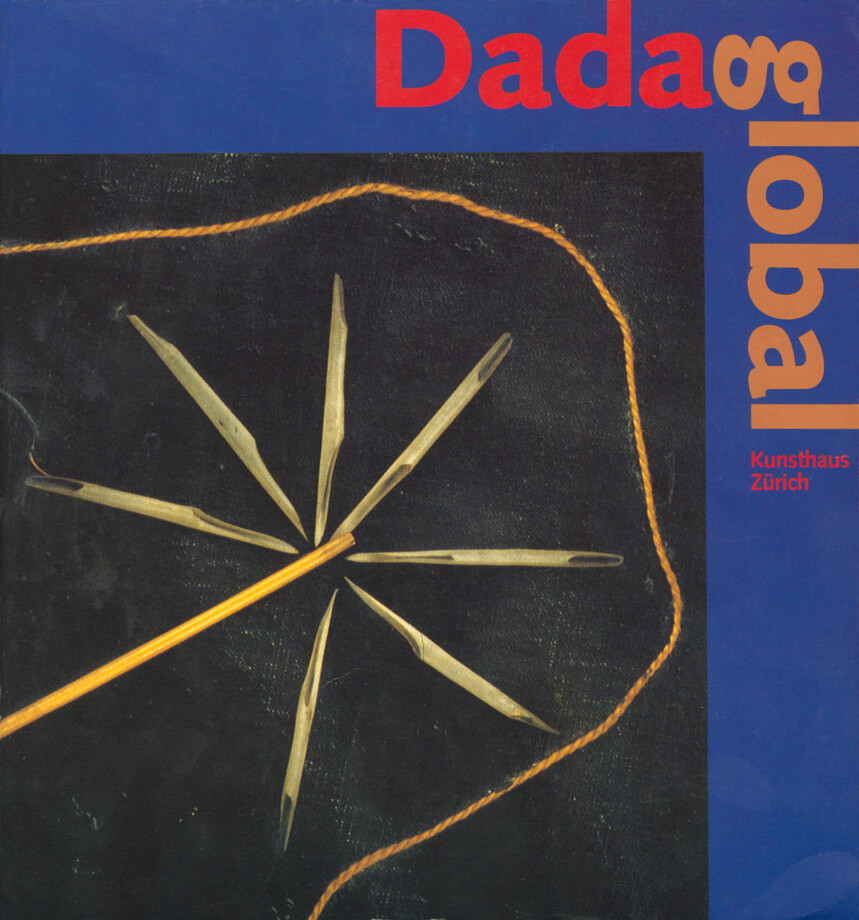

Unparalleled in its kind for Zurich, the exhibition presented in 1980 was the prelude to the commitment to Dada shown by the subsequent deputy director of the Kunsthaus, Guido Magnaguagno. Together with Felix Baumann and members of the collection committee and the Zürcher Kunstfreunde association (VZK) he succeeded in ensuring further focused purchases and exhibitions as well as their documentation in the collection booklets of the Kunsthaus. These endeavors culminated in the comprehensive show Dada global in 1994. Throughout many years, Kunsthaus curator Harald Szeemann has also left a number of larger and smaller Dada trails to be picked up with his exhibitions on the colony of Monte Verità, on the subject of the gesamtkunstwerk, on Alfred Jarry, Suzanne Perrottet, and Mary Wigman.

Exhibition Dada in Zürich, 1980

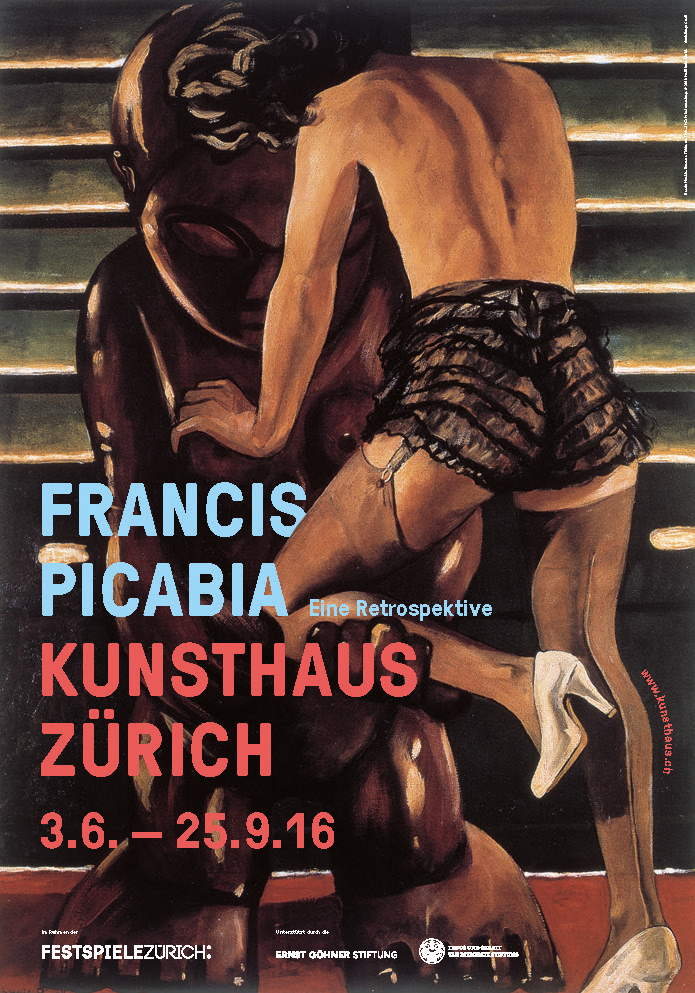

The following two decades saw selective further additions to the collection’s holdings such as André Breton’s Dossier Dada, which was presented in an exhibition curated by Tobia Bezzola in 2005, and a number of acquisitions in the run-up to the Cabaret Voltaire centennial of 2016 initiated by the exhibitions Dadaglobe Reconstructed and Picabia. A Retrospective as well as research on the subject. These impulses fall under the directorship of Christoph Becker. In view of the anniversary year, Kurt Schwitters’ Huthbild of 1919, which the Giedions had purchased from Schwitters after the exhibition in 1929, was donated to the Kunsthaus. This early collage has thus found its home in the place where it has been presented to the public on various occasions such as in the context of the exhibition Carola Giedion-Welcker und die Moderne (Carola Giedion-Welcker and Modernism) curated by Cathérine Hug in 2007.

The Dada collection in the Kunsthaus Zürich has world standing. It captivates people with its range and depth, the latter particularly as regards Dada Zurich. More than one hundred documents and seventy works perfectly illustrate and document the entire “chronique zurichoise.” The majority of items in the collection, another one hundred and thirty works and three hundred and fifty documents, offer a survey of the Dadaist epicenters and their offshoots and forge a “dadaglobal” bridge from 1915 to 1925. It has been of paramount importance from the very beginning to collect Dada on such a wide spatial and temporal scale. It was not the casual dadaistic motto “Dada est tatou tout est dada” (Tristan Tzara, 1916) which determined the direction to be taken but rather the assessment that the Mouvement Dada could only emerge and unfold its impact as a heterogeneous international phenomenon. This approach does not negate the question after the Dadaist core but breathes new life into it again and again.

Felix Baumann on Dadaism, 2015

Felix Baumann curated the exhibition presented at the Kunsthaus Zürich on the occasion of Dada’s fiftieth anniversary in 1966. His time as director of the Kunsthaus (1976–2000) saw a number of further important Dada exhibitions such as Dada in Zürich in 1980 and Dada global in 1994. The core of the institution’s holdings in the field of Dadaism was acquired under his directorship. In this interview conducted in the autumn of 2015, Felix Baumann reminisces about these years, answering questions of Kunsthaus curator Cathérine Hug, Dada expert Raimund Meyer, and art historian Manuela Reissmann.

Hans Bolliger on Dadaism, 1994

Hans Bolliger (1915–2002) was a key figure in the historiography of Dadaism in Zurich and in fostering its understanding. The bookseller and antiquarian came to research and collect Dadaist works of art and documents quite early on in his career. A large part of his collection is in the possession of the Kunsthaus Zürich today. He contributed substantially to the exhibitions Dada in Zürich and Dada global at the Kunsthaus in 1980 and 1994, respectively as well as to the publications Dada in Zürich (1985) und Dada global (1994). This interview was shot on the occasion of the exhibition Dada global by Peter Münger in 1994. The questions were asked by Juri Steiner.

Exhibitions at Kunsthaus Zürich 1910–2016 (Selection with reference to Dada)

Moderner Bund

[U. a. Hans Arp, Oscar Lüthy]

07.07.1912 – 31.07.1912

Schweizerische Expressionisten "Das Neue Leben"

[U. a. Hans Arp, Alice Bailly, Augusto Giacometti, Marcel Janco, Francis Picabia, Sophie Taeuber]

12.01.1919 – 05.02.1919

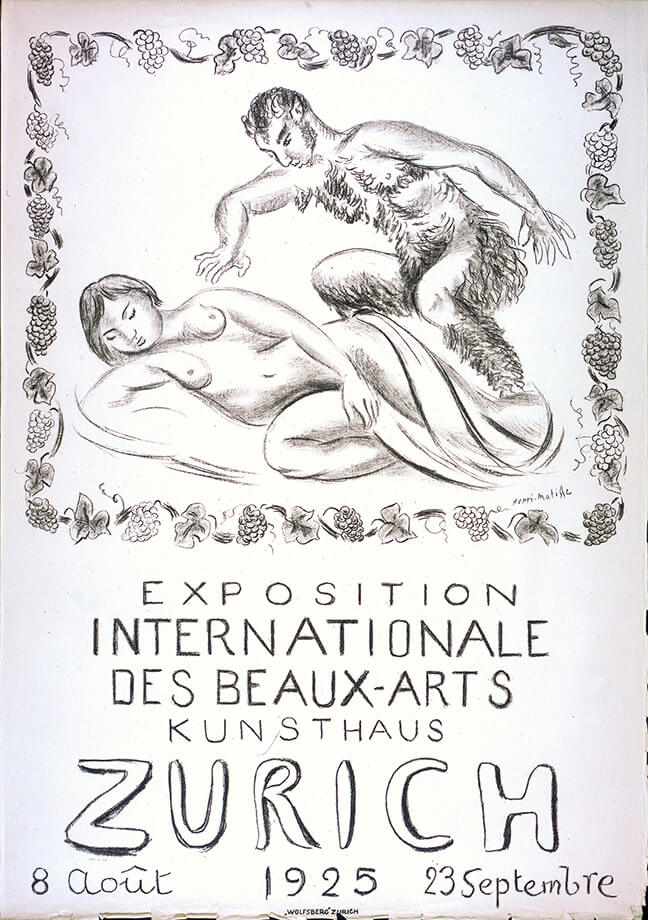

Internationale Ausstellung

[U. a. Otto Dix, Georg Grosz]

08.08.1925 – 30.09.1925

Poster design: Henri Matisse

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© Succession H. Matisse / 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

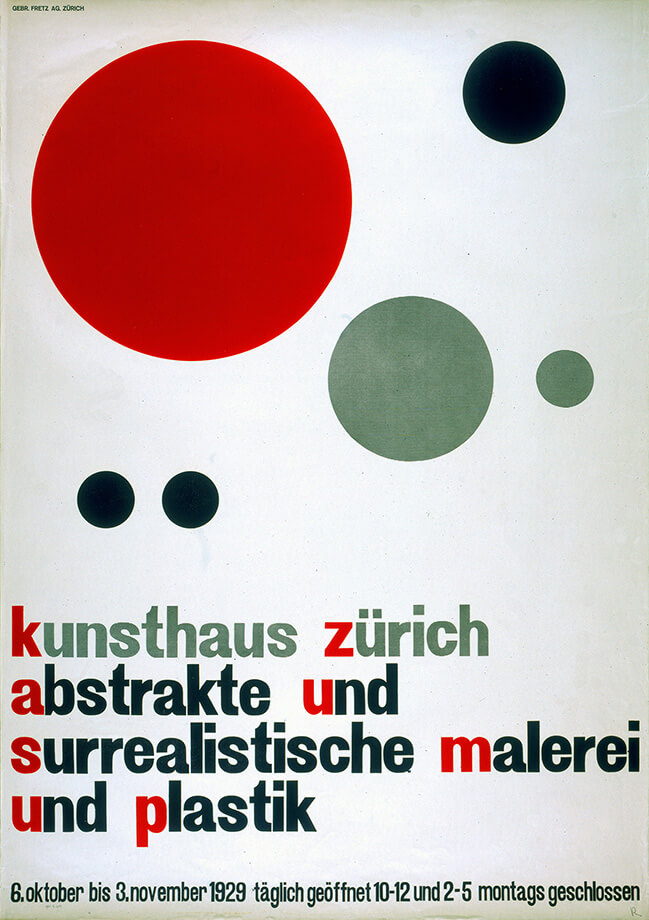

Abstrakte und surrealistische Malerei und Plastik

[U. a. Hans Arp, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Francis Picabia, Kurt Schwitters]

06.10.1929 – 03.11.1929

Poster design: Hans Arp, Walter Cyliax

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

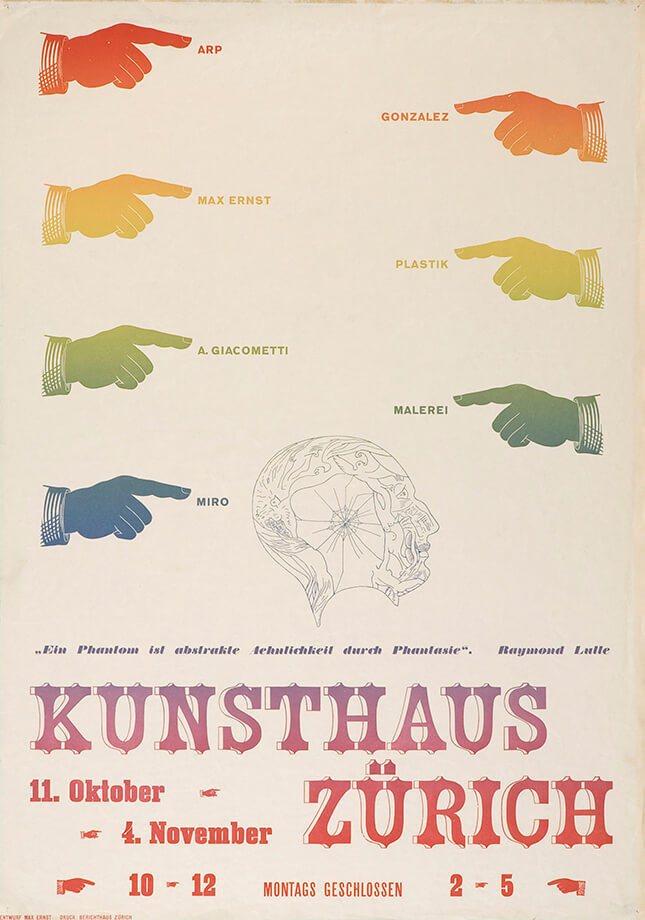

Abstrakte Malerei und Plastik

[U. a. Hans Arp, Max Ernst, Alberto Giacometti, José Gonzalez, Joan Mirò. Katalogvorwort: Max Ernst]

11.10.1934 – 04.11.1934

Poster design: Max Ernst

Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Plakatsammlung

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

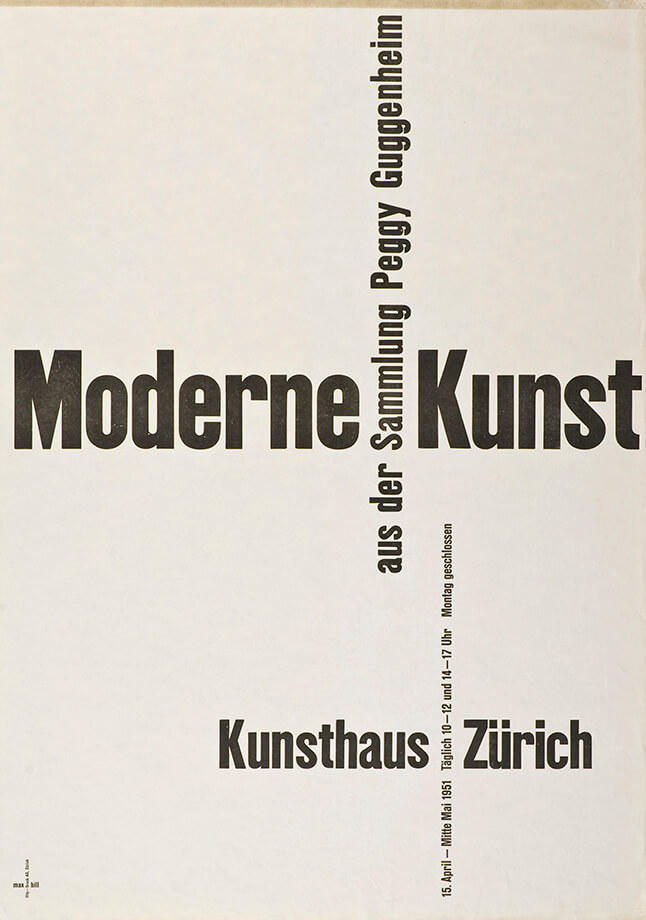

Moderne Kunst aus der Sammlung Peggy Guggenheim

[U. a. Hans Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Max Ernst, Raoul Hausmann, Francis Picabia, Man Ray, Kurt Schwitters]

15.04.1951 – 14.05.1951

Poster design: Max Bill

Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Plakatsammlung

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

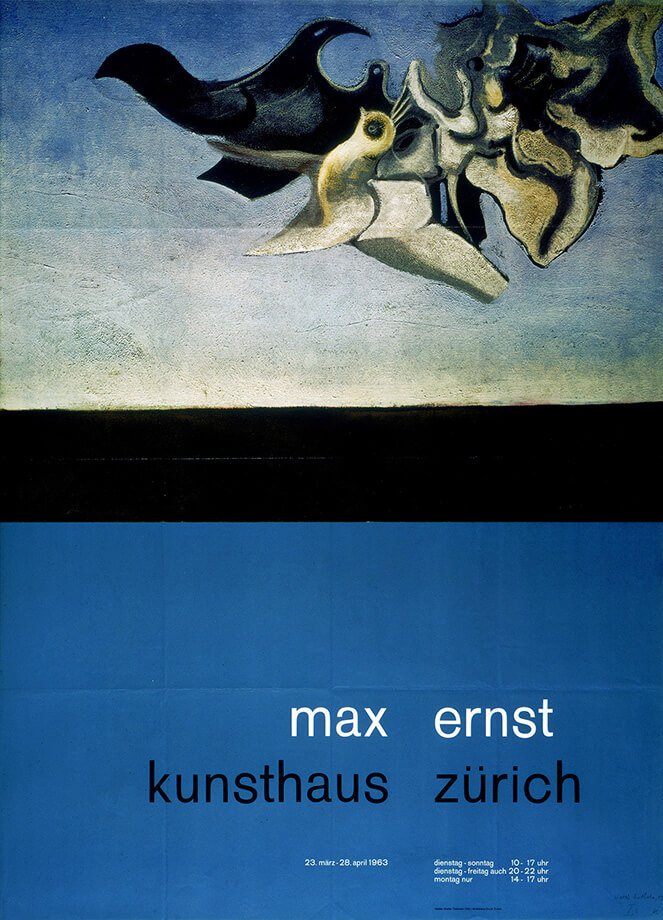

Max Ernst

23.03.1963 – 28.04.1963

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

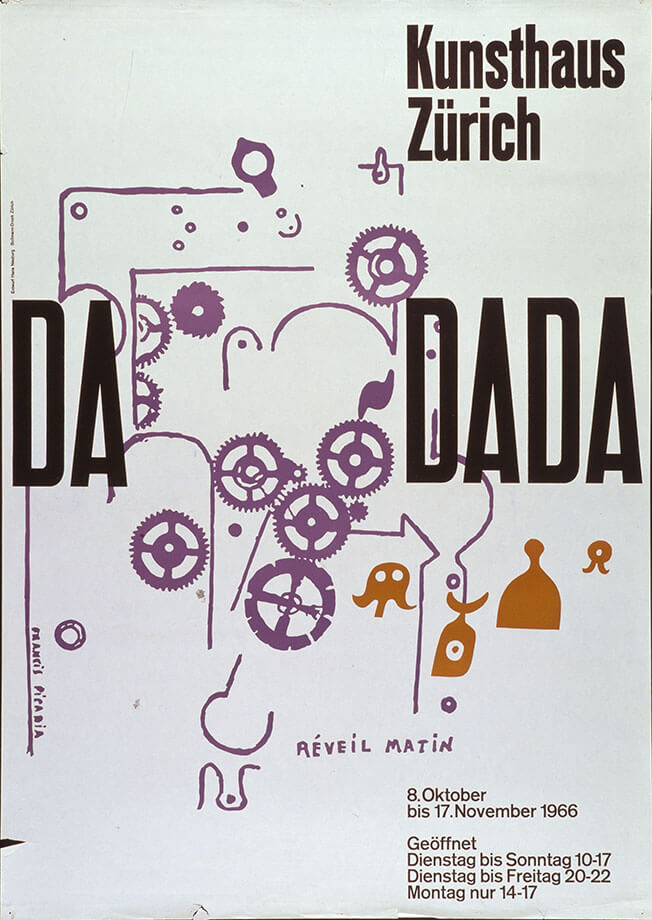

DADA-Ausstellung zum 50-jährigen Jubiläum

08.10.1966 – 17.11.1966

Poster design: Hans Neuburg

Zürcher Hochschule der Künste, Museum für Gestaltung Zürich, Plakatsammlung

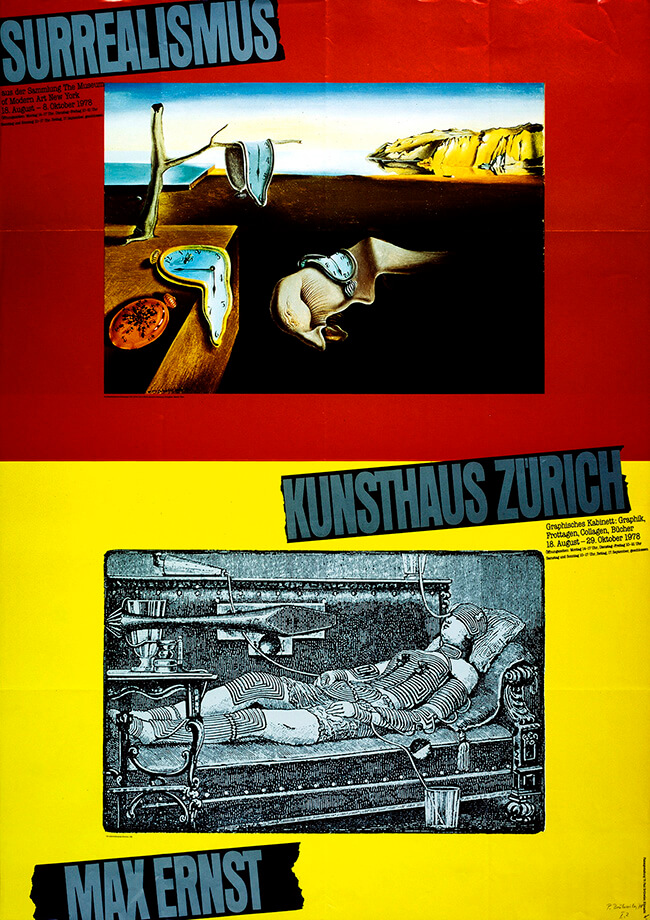

Max Ernst

Frottagen, Collagen, Zeichnungen, Graphik und Bücher

18.08.1978 – 29.10.1978

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

Monte Verità

17.11.1978 – 28.01.1979

Poster design: Paul Brühwiler, Küsnacht

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

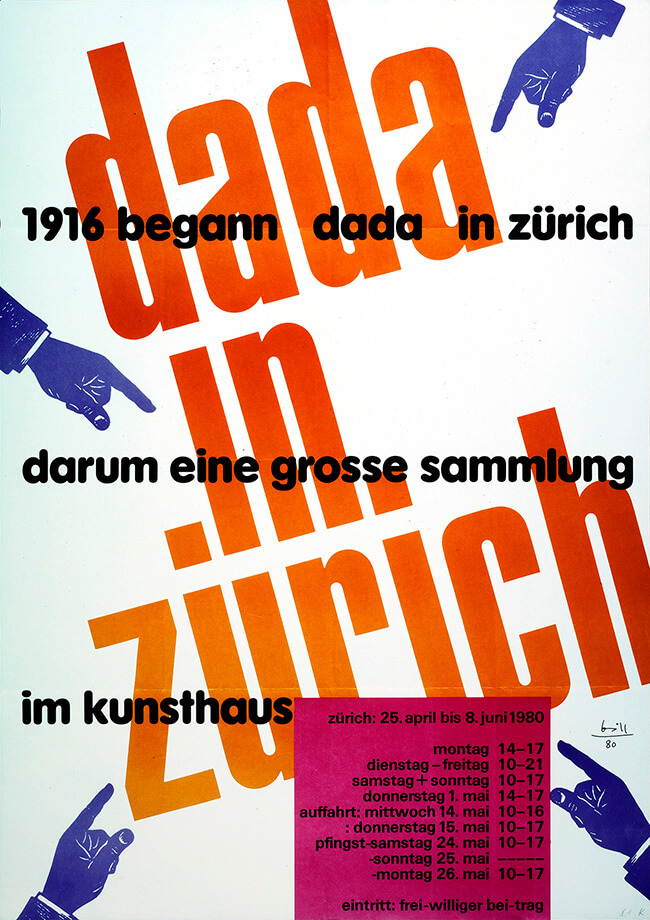

DADA in Zürich

25.04.1980 – 08.06.1980

Poster design: Max Bill

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

Hans Richter

16.04.1982 – 23.05.1982

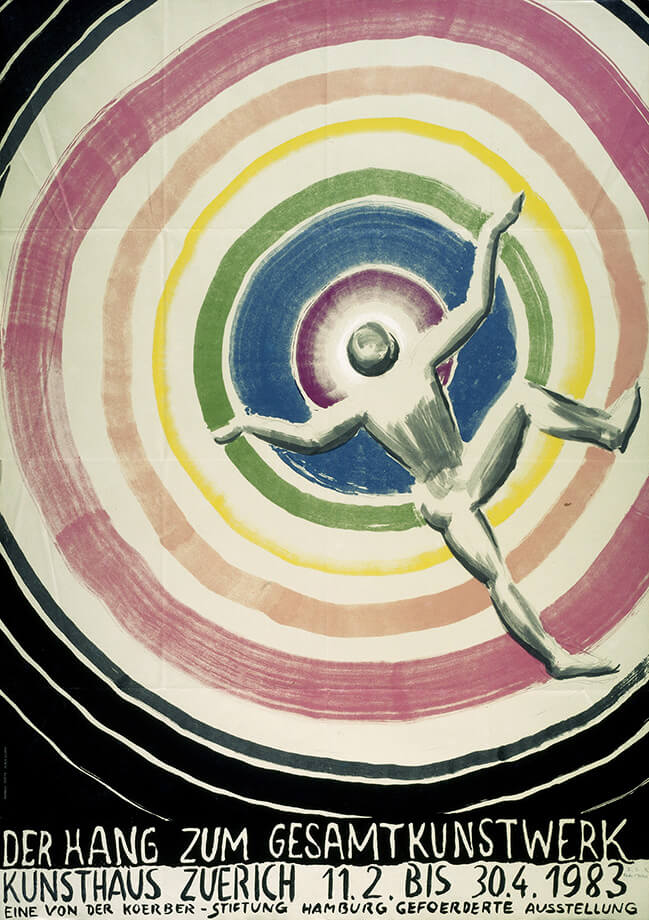

Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk

[U. a. Marcel Duchamp, Francis Picabia, Erik Satie, Dada Zürich und Berlin, Kurt Schwitters, Rudolf von Laban]

11.02.1983 – 30.04.1983

Poster design: Markus Raetz

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

Francis Picabia

03.02.1984 – 25.03.1984

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

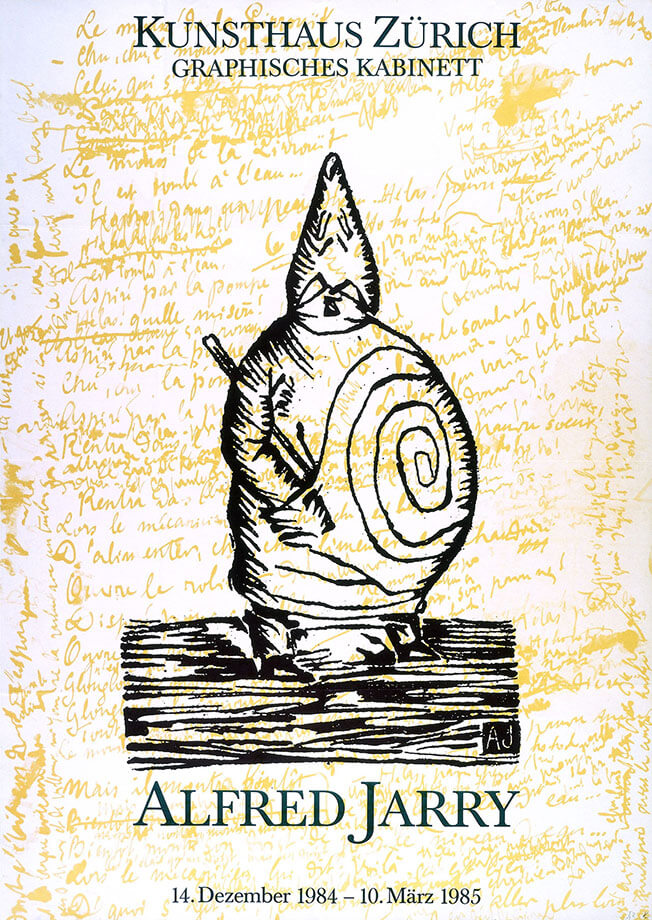

Alfred Jarry und die Pataphysik

14.12.1984 – 10.03.1985

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

Hans Arp und Hugo Ball zum 100. Geburtstag

05.07.1986 – 07.09.1986

Poster design: Josef Müller-Brockmann

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich

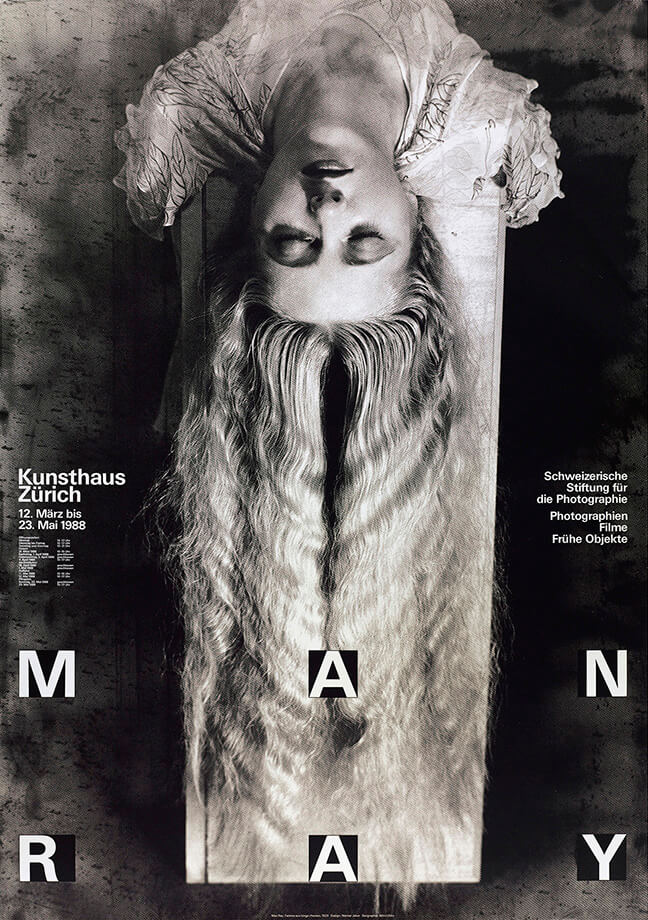

Man Ray

Photographien – Filme – Frühe Objekte

12.03.1988 – 23.05.1988

Poster design: Werner Jeker

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

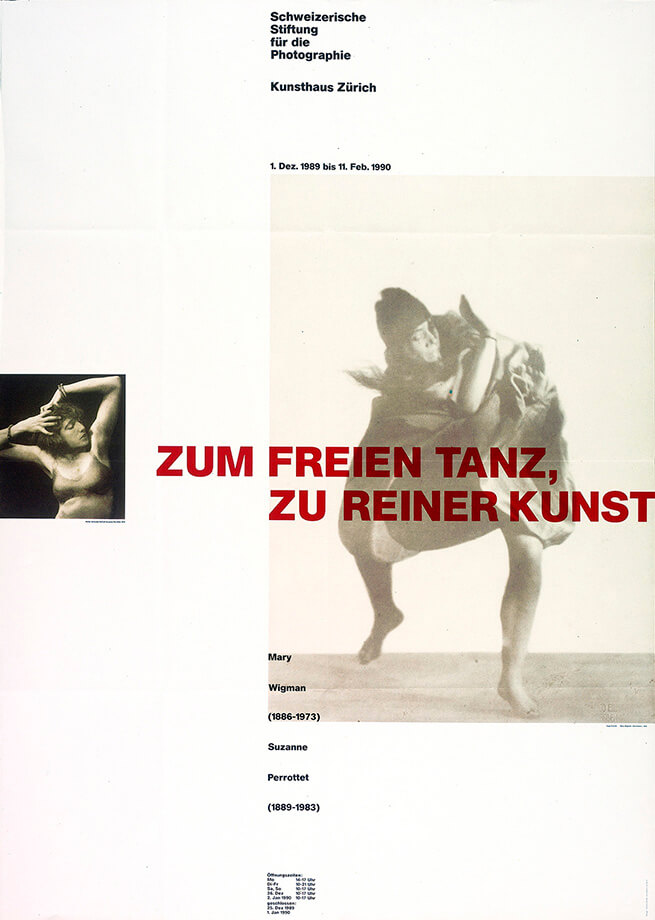

Zum freien Tanz, zu reiner Kunst

Suzanne Perrottet (1889 – 1983) und Mary Wigman (1886 – 1973)

01.12.1989 – 11.02.1990

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

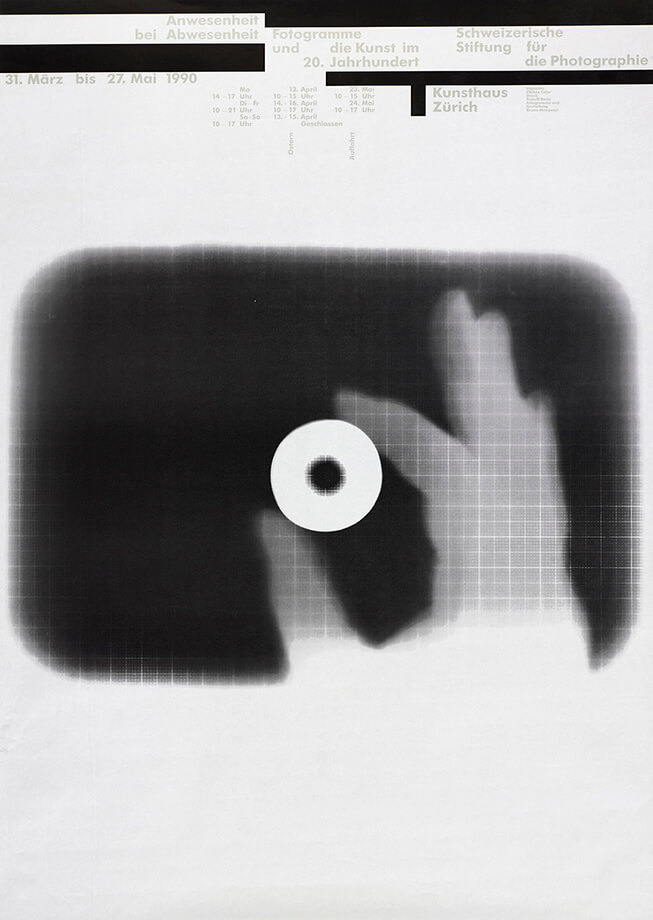

Anwesenheit bei Abwesenheit. Fotogramme in der Kunst des 20. Jahrhunderts

[U. a. Raoul Hausmann, Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, Man Ray, Christian Schad]

31.03.1990 – 27.05.1990

Poster design: Bruno Monguzzi

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

DADA global

12.08.1994 – 06.11.1994

Poster design: Josef Müller-Brockmann

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 Museum für Gestaltung, Zürich

Erwin Blumenfeld. A Fetish for Beauty

17.01.1997 – 23.03.1997

Poster design: Egon Meichtry, Zürich

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© Yorick Blumenfeld

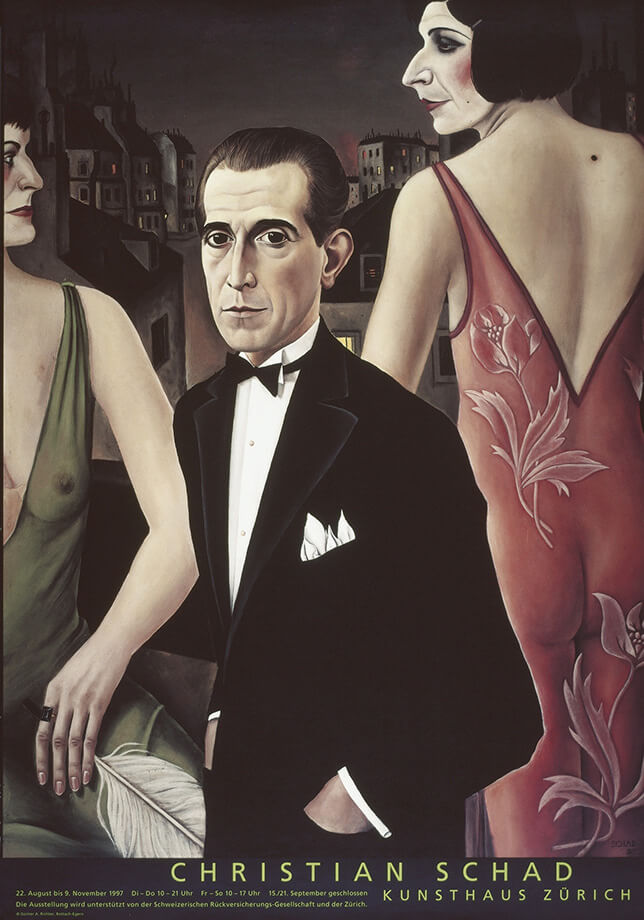

Christian Schad 1894 – 1982

22.08.1997 – 09.11.1997

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich

© Günter A. Richter, Rottach-Egern

Arnold Böcklin, Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst. Eine Reise ins Ungewisse

03.10.1997 – 18.01.1998

Carte-de-visite 3. DADA-Revival(s)

08.04.2000 – 21.05.2000

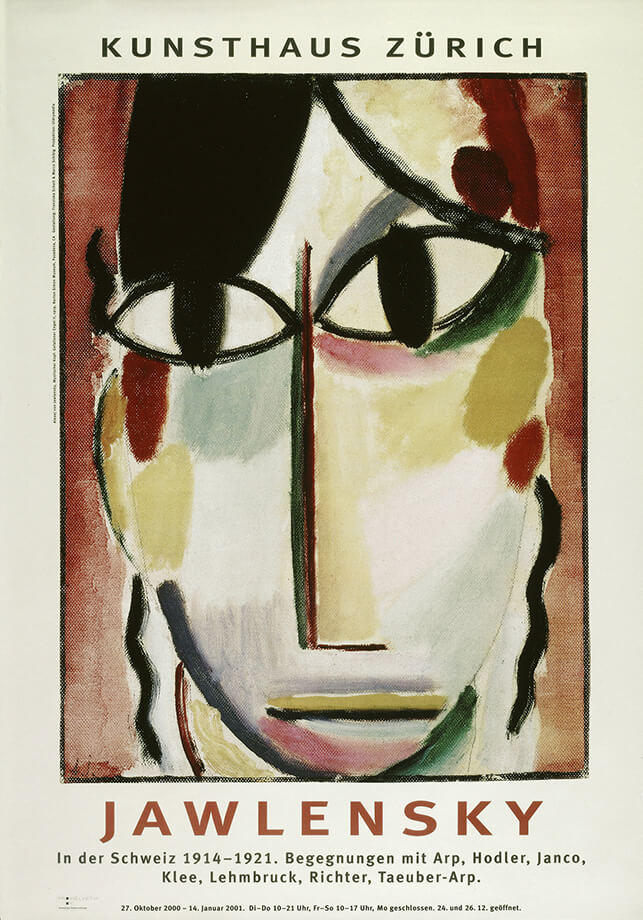

Jawlensky in der Schweiz 1914 – 1921. Begegnungen mit Hodler, Klee, Arp, Taeuber-Arp, Janco, Richter, Lehmbruck

27.10.2000 – 14.01.2001

Poster design: Franziska Schott, Marco Schibig

Schweizerische Nationalbibliothek / NB, Graphische Sammlung, Bern

André Breton. Dossier DADA

09.12.2005 – 19.02.2006

Carola Giedion-Welcker und die Moderne

[U. a. Arp, Schwitters]

31.08.2007 – 18.11.2007

Dadaglobe Reconstructed

05.01.2016 – 01.05.2016

Subsequently shown at The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Poster Design: NORM

New and Surprising Items from the Collection: Supplément Dada

20.05.2016 – 24.07.2016

Francis Picabia. Eine Retrospektive

03.06.2016 – 25.09.2016

In collaboration with The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Poster Design: Crafft

© 2016 ProLitteris, Zürich