The Dadaists’ first publication dates from late May 1916 and was issued on the occasion of a soirée. The Recueil littéraire et artistique (collection of literary and artistic contributions) documents their activities in the early phase of Cabaret Voltaire. In his introductory text, Hugo Ball defines the Cabaret as an independent place beyond war and nationalist fatherlands—a feature he also emphasized in his editorial notes. The word Dada appears in this booklet for the first time, which is why the venue is regarded as the official birthplace of Dadaism. While Hugo Ball announces an international magazine titled Dada in his introduction, Tristan Tzara and Richard Huelsenbeck playfully lay the first cornerstones for the Dada myth in their dialogue: “Olululu Olululu Dada ist gross Dada ist schön” (Olululu Olululu Dada is great Dada is beautiful).

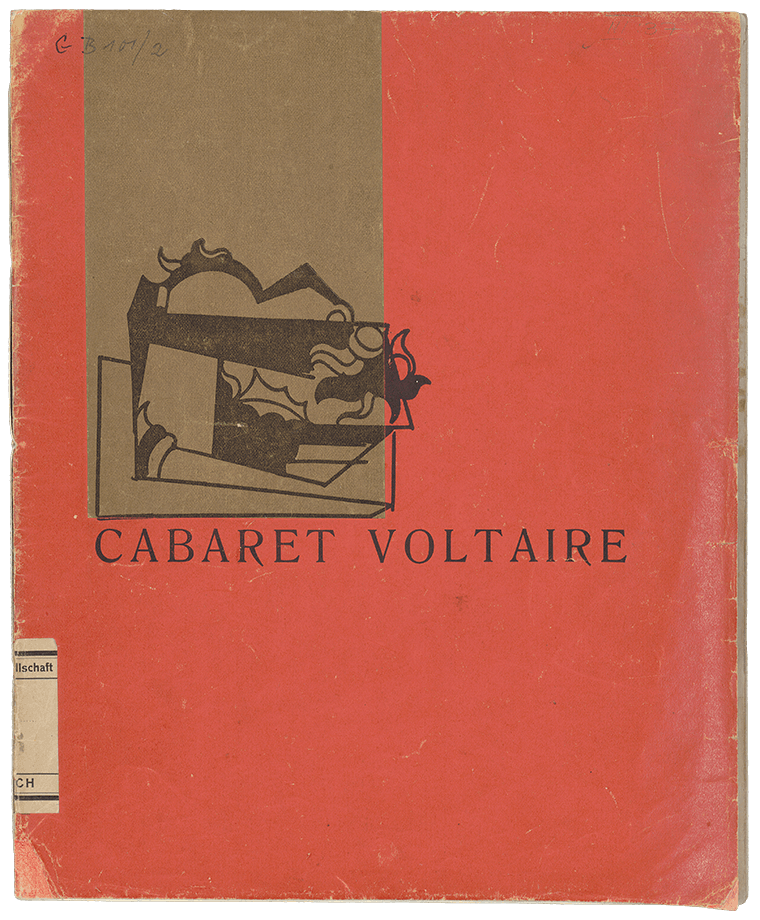

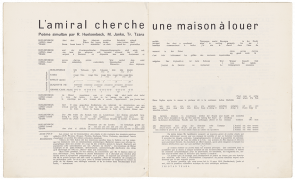

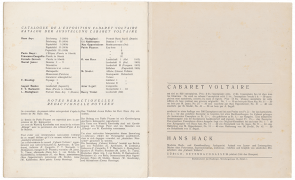

The belly band of the publication already hinted at the heterogeneous character of Cabaret Voltaire: “Futurisme Cubisme Expressionisme.” The exhibition presented there, which was accompanied by a “catalogue” in the booklet, was also committed to the various new tendencies. Different contributions testify to the Dadaists’ affiliation with French and Italian modernism. Dada-specific texts and illustrations in the booklet comprise the trilingual simultaneous poem “L’amiral cherche une maison à louer” (The admiral looks for a house to rent) with its final result “L’amiral n’a rien trouvé” (The admiral has not found anything) brought forth in unison, works by Otto van Rees and Hans Arp (Papierbild [Paper Picture], Teppich [Carpet]), as well as references to “negro art” (Affiche pour le Chant nègre [poster for Negro Song]) by Marcel Janco. The attention to cover design and the issue of variants or luxury editions frequently resulting from it became a characteristic of Zurich Dada publications.

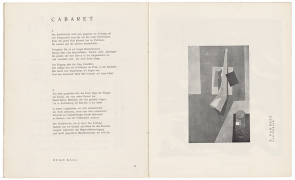

The cabaret seated fifty people at tables laid in red and had some benches on the sides; the walls were painted blue, the ceiling black. The place was probably furnished with lamps with red and green shades. The stage was small, “much too small to provide space for any boredom” (Züricher Post), and there was a black piano in a corner, “lying in wait like a beast” (Han Coray). The black-and-white photograph of the oil painting Cabaret Voltaire by Marcel Janco that disappeared in 1925 and its later replicas are the only visual documents of the cabaret’s furnishings and ambience.

Edition: Cabaret Voltaire was published in an edition of five hundred copies in French and German, with a smaller number of German issues (Hugo Ball’s introductory text in German, stapled (1.–/2.– CHF)) or with a paper cover (2.–/3.– CHF). The announced numbered special edition of fifty copies was probably never printed. The outside of the sturdy white paper cover designed by Arp was dyed red, the vertical gold foil strip applied shows a drawing by Hans Arp, printed in black. There are also some copies with a silver foil with the outside of the cover dyed blue. The copy in the collection of the Kunsthaus Zürich is a German issue without a belly band.

Provenance: Cabaret Voltaire was purchased by the Kunsthaus Zürich at the auction “Items from the Library and Collection of Tristan Tzara (Kornfeld & Klipstein, Dokumentations-Bibliothek III, Bern)” in 1968.

→ Marcel Słodki, poster for the opening of the Künstlerkneipe Voltaire, Gr.Inv. 1992/39

→ Karl Schlegel, invitation card for the opening of the Künstler-Kneipe Voltaire, DADA V:49

→ Marcel Janco, poster design for Chant nègre [Negro Song], DADA V:47

→ Bergmann & Co., advertisements “Dada Haarwasser” [Dada hair tonic]¨and “Dada Kopfwasser [Dada scalp tonic], DADA V:64:1 and DADA V:64:2

→ Emmy Hennings, letter to Reinhold Rudolf Junghanns, DADA II:27

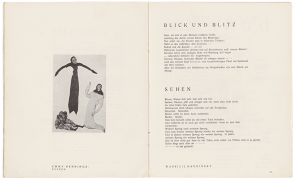

→ Emmy Hennings, Gedichte [Poems], DADA II:1

→ Hugo Ball, Ein Krippenspiel [A Nativity Play], DADA II:5

→ Hans Richter, Kaiser Wilhelm als Befehlshaber des Todes [Emperor Wilhelm as the Commander of Death], Z.Inv. 1977/44