Hans Richter had been drafted shortly after the outbreak of the First World War, yet was released from military service after only a few months because of a serious injury. In autumn 1916, he followed the medical advice to have his war wound treated in Switzerland. This also made it possible for him to keep a promise he had made: according to his own statement he had agreed upon meeting Albert Ehrenstein and Ferdinand Hardekopf in the Café de la Terrasse in Zurich two years after his conscription. This is where he met his old friends again and made new ones: Tristan Tzara as well as Marcel and Jules Janco.

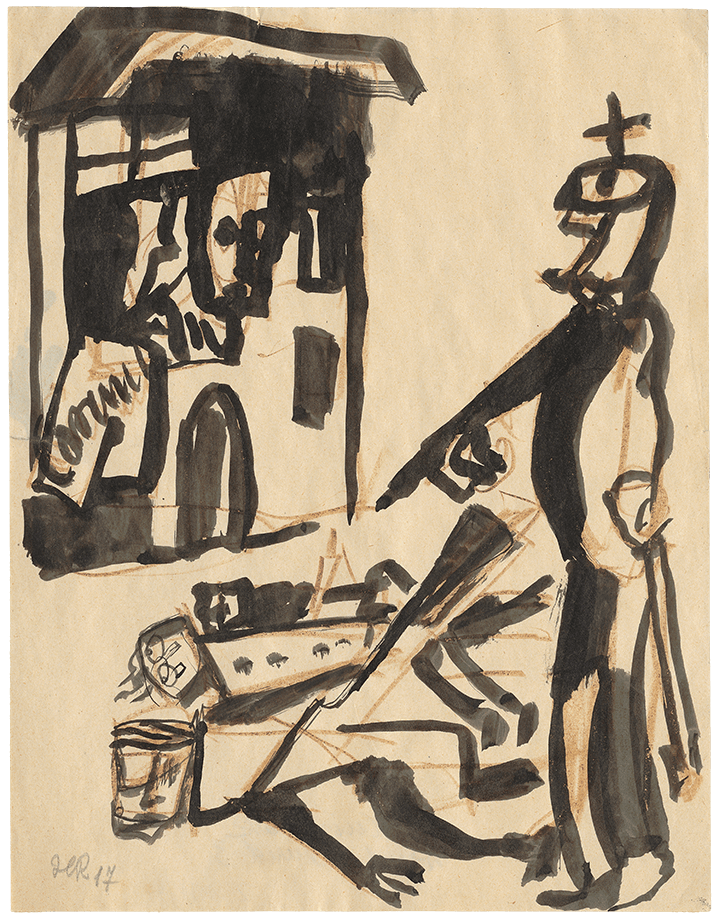

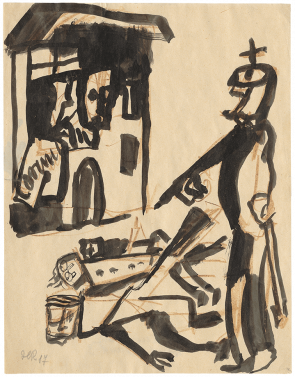

Richter confronted the barbarisms of his time with renewed strength, seeking political confrontation in using his crayon and pen to accuse and provoke. Kaiser Wilhelm als Befehlshaber des Todes depicts the ruler towering over struck-down figures in an erect pose; those who did not bow to the Emperor’s orders were left to choose between death and imprisonment. The series Die Welt den Ochsen und den Schweinen (The World between the Ox and the Swine) and Im Felde der Ehre (On the Field of Honour) produced in Zurich at that time portray warmongers and their victims in a wild, expressive manner. All these drawings of 1917 may be read as a continuation of the Totentanz (Dance of Death) performed to the accompaniment of a march melody in the Cabaret Voltaire, as a sequel imbued with equal scorn and derision. Richter’s drawings intended as illustrations were not published as such because of the metaphorical, difficult character of his pictorial language. This also holds true for his drawings Emmy Hennings im Gefängnis (Emmy Hennings in Prison), which were not used for Hennings’s novel Gefängnis (Prison, 1919).

In his text “Ein Maler spricht zu den Malern” (A Painter Speaks to the Painters, Zeit-Echo) Richter addressed the artist’s social responsibility. “How to answer for the terrible and mind-forsaken state of affairs without bringing up your entire whining, paining, and screaming in a way as articulate as you are, as precise as the ragingly honed awareness of guilt and injustice allows the culprits and good people.” Richter’s quest for the new man he depicted in his series Der heilige Mitmensch (The Holy Fellow Creature) activated him for the revolutionary political movements in Germany. His engagement influenced the artistic discussions in the Zurich circle of Dadaists and resulted in the Manifesto of the “Radikale Künstler / artistes radicaux” ( Radical Artists), of 1919 drawn up by Richter and signed by Hans Arp, Viking Eggeling, Marcel Janco, and others: “We artists, as representatives of an essential part of the entire culture, want to position ourselves ‘in the midst of things’ and take our share of responsibility for the future ideal development in the State.” The balancing act between the seriousness of the manifesto and Dadaist gestures reveals the personal and artistic tensions prevailing towards the end of Dada Zurich. Richter’s message Gegen Ohne Für Dada (Against Without For Dada), which he read out during the last Dada soirée in April 1919, reflects his ambivalent attitude towards this “moonstone-coloured Dada.”

Provenance: Donation from Frida Richter from the artist’s estate, 1977. The Kunsthaus Zürich’s holdings comprise forty-one drawings by Hans Richter from 1916 to 1918. First exhibitions: Providence, Museum of Modern Art, a.o., The World between the Ox and the Swine, 1971/1972; Zurich, Kunsthaus, Dada in Zürich, 1980; Berlin, Akademie der Künste, Zurich, Kunsthaus, Munich, Städtische Galerie, Hans Richter, 1982.

→ Hans Richter, Dada-Kopf [Dada Head], Z.Inv. 1977/64

→ Hans Richter, poster design for the 1st Dada Exhibition at the Galerie Corray, DADA V:80

→ Viking Eggeling, Komposition, Z.Inv. 1970/2