With Christian Schad, the Dada scene shifted from Zurich to Geneva, the second Dada capital in neutral Switzerland during the First World War. In Zurich itself, where Schad had arrived as a refugee in autumn 1915, he created in a close personal and artistic relationship with Marcel Słodki a comprehensive work of graphic art which was exhibited in galleries and with which he informed and supported the pre-Dadaist journal Sirius edited by Walter Serner. Without ever having taken part in the events at the Cabaret Voltaire, he moved on to Geneva in late 1916 to “dadaize” on the side of Serner, his “seul et meilleur ami” (only and best friend), the city on the Rhone in 1919/20 with exhibitions and a “Bal Dada.” Serner in turn did his best to create all-out stupefaction by spreading hoaxes that falsely portended an upcoming Dada World Congress. He took his directions from his own manifesto Letzte Lockerung (Last Loosening).

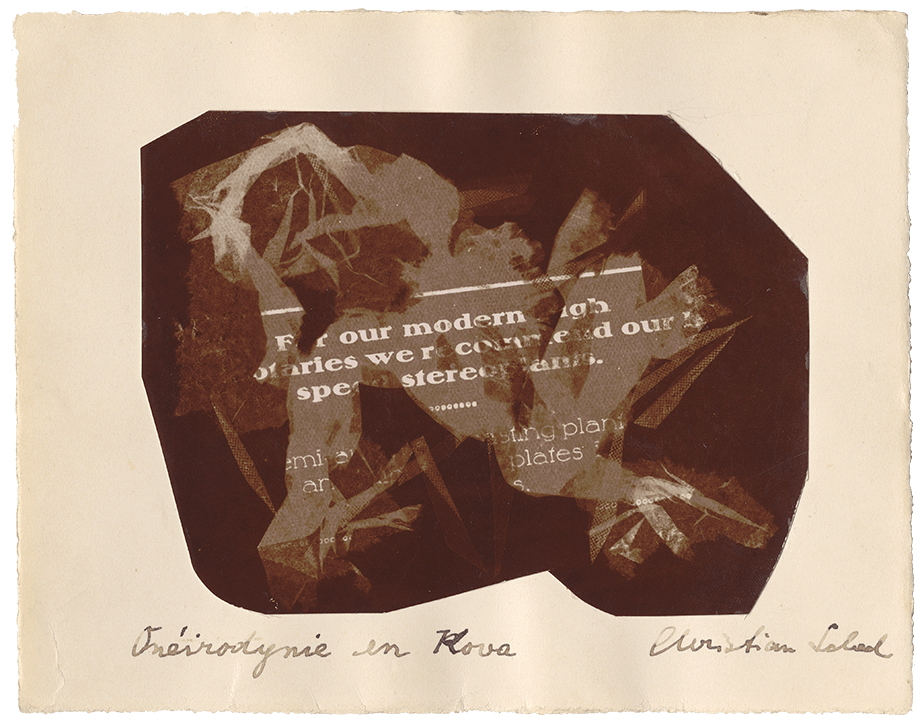

The decisive step towards abstraction was taken by Schad in a series of woodcuts. Tzara had them sent to him from the Geneva branch of Dada to use them for the luxury editions of Dada 4–5 and Der Zeltweg (both 1919). An artistic breakthrough came for Schad with his photographic experiments which led to a series of thirty-one photograms in autumn 1919. These “photographs without camera,” for which random objects were placed on light-sensitive paper and then exposed to light, were nothing new, but dated back to the beginnings of photography. However, their rediscovery by Schad—and not long after by Man Ray and László Moholy-Nagy—brought about a qualitative leap forward in photography with a lasting effect. The Dadaist point of the matter was in the random choice of everyday materials and their ostensibly accidental array, with pictorial effect only influenceable to a limited extent. Serner and Tzara understood the significance of this play of photographic miniatures right away. As a sly portrait shot, one such “schadograph,” as Tristan Tzara later came to call Schad’s photograms, appeared in Dada 7 (Dadaphone, March 1920). Its title, Arp et Val Serner dans le crocodarium royal de Londres, transcends the banality of what is going on “maybe into the dream-like, maybe into nothingness” (Schad)—it remains enigmatic like Onéirodynie en Kova.

With his wood reliefs, which exceeded any usual picture size (as with Hans Arp and Marcel Janco), Schad again gave proof of his ongoing intense search for new creative possibilities. Turning away from oil painting, he relied on Ripolin, a technoid enamel, for his reliefs. Their irregular basic shapes and the everyday objects occasionally applied to them intimate that they were related to the “schadographs.” While the reliefs remained stored away in some shed in Geneva for forty-five years and were temporarily considered lost, the “schadographs” were safe with Tzara. The usurping propagator and maniacal collector ignored Schad’s attempts to claim them back and kept the “schadographs” throughout his lifetime. Decades later, the fascination of the photogram technique caught up with Schad again, and he started expanding his “schadographic” oeuvre again from the 1960s.

Marked in pencil on the back of the cardboard: “T. T. [Tristan Tzara].” The holdings of the Kunsthaus Zürich include four “schadographs” from 1918. Provenance: Donation from Hans Bolliger to the Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde (Association of Friends of the Kunsthaus). 1965 acquired by Bolliger in a swap deal with Tristan Tzara against a copy of the poster for the soirée of Tristan Tzara at the Zunfthaus zur Meisen, DADA V:47.

First exhibitions: Düsseldorf, Kunsthalle, Dada. Dokumente einer Bewegung, 1958. Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Dada, 1958/1959. Berlin, Akademie der Künste, Tendenzen der Zwanziger Jahre, 1977. Zürich, Kunsthaus, Dada in Zürich, 1980.

→ Marcel Słodki, poster for the opening of the Künstlerkneipe Voltaire, Gr.Inv. 1992/39

→ Marcel Janco, poster for the soirée of Tristan Tzara at the Zunfthaus zur Meisen, DADA V:47