Emmy Hennings already had a lot of stage experience when she came to Zurich in the spring of 1915. Here, she was the grand diseuse, the life and soul of whatever was going on—“the star of so many nights of cabarets and poems!” (Züricher Post), shocking the audience when she sang Hugo Ball’s Totentanz (Dance of Death), arousing it when she lent her body to verses, entertaining it with ballads by Wedekind, chansons by Aristide Bruant, or Danish folksongs, and calming it by reading prose texts. When the cabaret programme came to a standstill she stepped in successfully. And she did so even when she, lacking a passport, could not leave the country after her mother’s death in whose care she had left her nine-year-old daughter.

For the “red notebook” Hennings typed up the poems she had published in such Zurich magazines as Die Aehre or Der Revoluzzer on a borrowed typewriter, put them between the two halves of a roughly hand-cut folded light cardboard, and sold these delicate notebooks in the Cabaret Voltaire, which was still called Künstlerkneipe Voltaire (artists’ bar Voltaire) at the time. This provided her with a small additional income like the postcards with the Totentanz song she offered for sale. Hennings’ first and only publication that had come out before was titled Die letzte Freude (The Last Joy, 1912), aimed at expressing her joy at seeing her poems printed. Though some poems in the “red notebook” also tell of joys, the collection rather shouts for bread and reveals inner misery. The poems are anything but simple variations of motives and themes typical of the time: whereas Gefängnis (Prison) relates to her imprisonments in Munich, which Hennings repeatedly tried to come to terms with in writing and Hans Richter captured in sketches and drawings, Aether (Ether) and Mädchen am Kai (Girl on the Quayside) sprang from the soul of the drug addict prostituting herself as portrayed by Reinhold Rudolf Junghanns. “Living in Zurich: rurally among morphinists”—Hugo Ball’s introductory sentence to his first impressions of Zurich, Die Weissen Blätter (The White Pages, 1915), had a very concrete background.

Only once, in a letter to Tristan Tzara written in March 1917, Hennings signed as “Your Hennings – Dada.” Hennings was both central and marginal for Dada Zurich. Her poetry was never Dada, yet her presence was vitally important for the Cabaret Voltaire, for the Galerie Dada, and for the founder of Dada, Hugo Ball. Despite her fleeting appearance she was the center for numerous people.

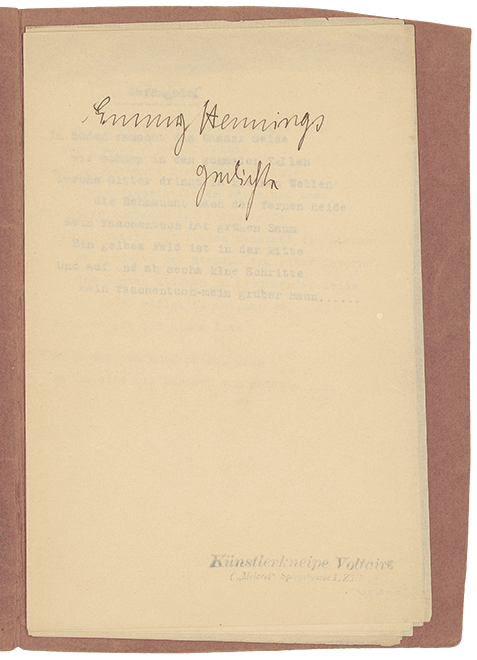

Edition: Unique copy. Booklets that are similar in form and content were published in the same edition and are of greatest rareness. Eight loose, unstapled A4 typewriter paper sheets folded in halves, in a reddish light cardboard cover roughly hand-cut with scissors. Title page signed and titled by Emmy Hennings in ink, address stamp at the bottom margin. Provenance: Hans Bolliger, Zurich, 1980.

→ Emmy Hennings, letter to Reinhold Rudolf Junghanns, DADA I:27

→ Cabaret Voltaire, DADA III:37

→ Marcel Słodki, poster for the opening of the Künstlerkneipe Voltaire, Gr.Inv. 1992/39

→ Karl Schlegel, invitation card for the opening of the Künstler-Kneipe Voltaire, DADA V:49