“Dada war da, bevor Dada da war” (Dada was there before there was Dada)—Hans Arp’s famous dictum applies not only to the movement, but to the word itself. It had long existed in dictionaries and in everyday language before the Dadaists reinvented it for their own purposes. “Dada means yes, yes in Romanian, gee-gee or hobbyhorse in French. To the Germans, it is a sign of silly naiveté and procreation-minded fondness for the baby carriage,” as Hugo Ball summed it up. Maybe a Larousse dictionary was indeed helpful in finding a name when Huelsenbeck and Ball were looking for one to give to a Cabaret singer, but maybe it was a whole different story. For example, the one recounted in Dada 8, a reverberation from Dada Tyrol:

“Declaration. I declare that Tristan Tzara found the word DADA on 8 February 1916, at 6 p.m.; I was present with my 12 children when Tzara pronounced that word for the first time, which unleashed rightful enthusiasm among us. This came to pass at the Café Terrasse in Zurich and I was carrying a brioche in my left nostril . . . Tarrenz near Imst 6 August 1921 ARP”

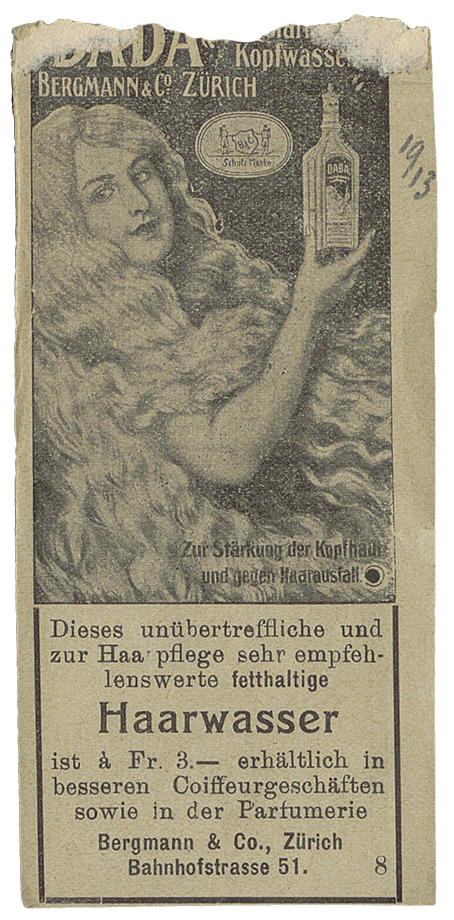

Officially and in print, the name first appeared in 1916 in the Cabaret Voltaire anthology, heralding the projected international Dada magazine. As soon as the golden two syllables were in the world, the Dadaists started using the word for their propaganda. It was free of content and—as noted by the Berlin Dadaists in 1919—meant nothing, that is, anything, and thus was ideally suited for that “foolery out of nothing that implicated all higher issues” (Hugo Ball). The play on words soon proved to be an ingenious artifice. Tzara was quick to realize that it could be put to good use to launch the larger international movement that he had in mind. Ball, on the other side, started analyzing these attitudes already in his Dada Manifesto of July 1916: “Just one word, and the word a movement . . . It is simply terrible. Making an art trend out of it must mean you want to get rid of complications.” At the same time, it was he who built the bridge to the Dada product line of the fine soap and perfume manufacturer Bergmann & Co. whose Dada hair tonic as well as their famous Dada Lily Milk Soap also were there before there was Dada. The company had been looking for an attractive internationally marketable name for their products, which were produced in Zurich and other places and were sold under the protected “Steckenpferd” (Hobbyhorse) brand, and had chosen the French translation. In the manifesto, Ball wrote, “Dada is the world soul, Dada is the clou, Dada is the best Lily Milk Soap in the world.” Not only did Bergmann produce Dada products, the company also provided its own very special type of Dada poetry in an advertising copy contest:

“Still looking twenty after all those years! / ‘How did you do it, speak, my dear?’ / It’s just three Francs to share that dream— / it’s Lily Milk Soap and Dada Cream!”

“Of many thousand soaps, you bet / ‘Bergmann’ is the one to get. / And of all fine creams they make / ‘Dada’ sure is best to take.”

Two advertisements from Swiss newspapers without any indication of source. With handwritten annual details in pencil (“1913”) and red ink (“1913/1914”). The ads were tear sheets put up in a company album of Bergmann & Co. Provenance: Donation from the family H.-R. u. V. Tobler-Renold, Zurich, 2015.