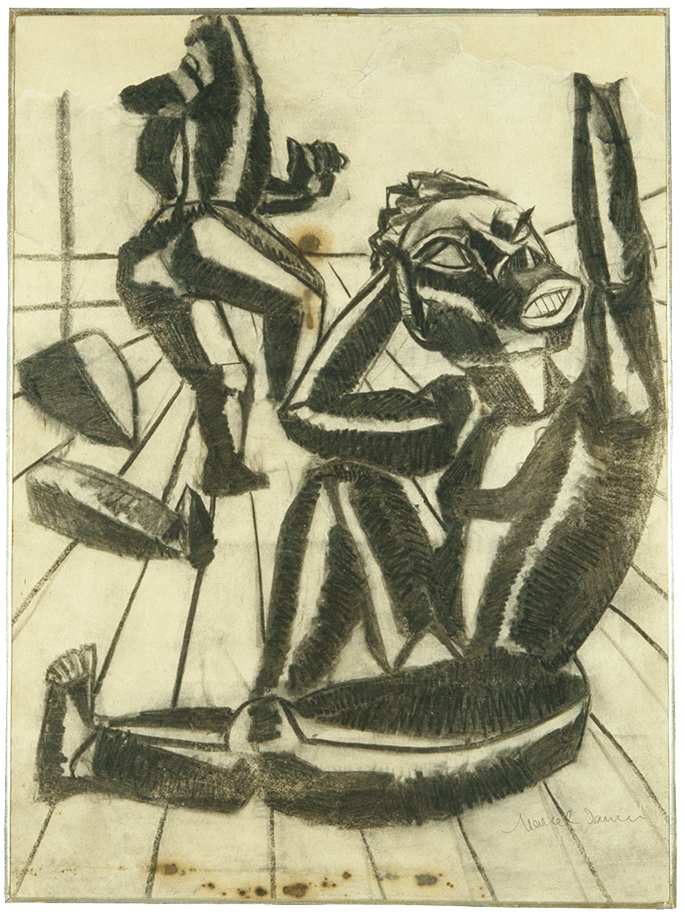

This poster design was created to publicize the performances of Chant nègre I and II (Negro Song I and II) at the Cabaret Voltaire and was reprinted in the Cabaret Voltaire anthology and some later program flyer. The fact that Marcel Janco then used his charcoal drawing once again as a cover illustration for the Romanian avant-garde journal Contimporanul reflects the great significance that the piece had for him. African and Oceanic art, poetry, and music were important sources of inspiration for Dada Zurich. In the quest for alternative ways in art, positive exploration of what had been referred to as “negro art” in the colonial period turned it into a store of novel forms. The Dadaists thus were in line with a tradition that had previously shown, for example, in the almanac Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider, 1912) or Carl Einstein’s study Negerplastik (Negro Sculpture, 1915). In Dada siegt! (Dada Wins!, 1920), Richard Huelsenbeck wrote about the “meaning of primitiveness—Dada, child’s babble, hey diddle diddle—the primitiveness which the epoch seemed to intimate through its predilection for negro sculpture, negro literature, and negro music.”

Whereas not much is known about Janco’s sources for his references to “negro art,” Tristan Tzara drew on research publications from the holdings of the city library for his “found and translated” verses. For the Chants nègres, which were performed in black frocks and with exotic drums, small and large, the Dadaists were supported by the principal of the Dada establishment, “who had long ago lived among African cultures for some time and, as an instructive and genial prima donna, warmly made every effort to help the performance” (Hugo Ball).

Janco’s exploration of extra-European cultures and imageries turned out particularly creative and productive when it came to designing masks and costumes. The effect of these masks made of painted cardboard, burlap, string and wire, which often covered more than just the face (and were electrically illuminated during the performance), was remarkable, both for the wearers and for the audience. Hugo Ball wrote, “We were all present when Janco arrived with his masks, and everybody immediately put one on. Then something strange happened. Not only did the mask immediately call for a costume, it also imposed a very specific and exalted way of carrying oneself that came close to lunacy. Without the slightest anticipation of this only five minutes ago, we were moving about in the most peculiar figures, draped and decked with all sorts of impossible things, each trying to outdo the other with their ideas.”

The top of the paper is damaged on both sides. A complete representation of the design is to be found on page 17 of Cabaret Voltaire and in the Programmblatt zur Sturm-Ausstellung II. Serie (Programme Leaflet for the Sturm Exhibition, 2nd series) Galerie Dada, 1917. Provenance: The poster design came up in the auction “Items from the Library and Collection of Tristan Tzara (Kornfeld & Klipstein, Dokumentations-Bibliothek III, Bern)” in 1968. In 1980, the Vereinigung Zürcher Kunstfreunde (Association of Friends of the Kunsthaus) purchased the piece for the Kunsthaus from a private collection.

First exhibitions: Düsseldorf, Kunsthalle, Dada. Dokumente einer Bewegung, 1958. Amsterdam, Stedelijk Museum, Dada, 1958/59. London, Arts Council, Dada and Surrealism reviewed, 1978.

→ Cabaret Voltaire, DADA III:37

→ Marcel Janco, poster for the soirée of Tristan Tzara at the Zunfthaus zur Meisen, DADA V:47

→ Dada 3, DADA III:33:3